15

he evolution of Ellicott City previewed the torrid growth

which lay ahead for Baltimore, where conditions were

coalescing to prime the Port’s pump. The textbook factors of

production were falling into place: labor, capital goods such as

machines, factories and infrastructure, and an entrepreneurial

class for organization and risk-taking.

Grain soon would overtake tobacco as Baltimore’s leading

export. Few know the name of John Stevenson, but a cargo of flour

this shipyard owner shipped to his native Ireland in 1750 proved

instrumental in putting Baltimore on the world map. The flour,

because it was pure andmold-resistant, was a resounding success in

Ireland. More overseas orders soon followed. Stevenson’s ambition

was to establish the Port of Baltimore as

the

flour exporter of

choice for foreign markets; many regard him as the maritime

pioneer whose vision was responsible for the bulk cargo trans-

actions for which the Port subsequently became famous.

Carved into the waterfront just downriver from Baltimore Town

lay Fell’s Point, whose cobble-stoned roadways and English street

names still evoke a quality of other-worldliness.

Even after Baltimore annexed Fell’s Point in 1773, the river

rivals remained a world apart in a sense, separated more by their

differences than real distance. Baltimore was but a backwater, with

little to recommend it except a rudimentary port, while Fell’s Point,

with its natural deep-water port, dealt in fast ships and fast times.

If relatively little is known about Baltimore or its port before the

Revolutionary War era, it’s because there was little worth knowing.

But that would change; Baltimore’s time was coming. Be-

tween 1752 and 1774, its housing stock increased from 24 to 564.

Baltimore became the county seat in 1768, taking the weighty

functions of local government — courts, jails and land records

— from Joppa Town. Cottage industry was complimented by new,

heavier industry, such as a clayworks supplying building brick for

a growing city. The quality and fine, natural color of Baltimore

brick made it highly desirable; as an export, it was said to gild the

front of opulent homes in Philadelphia, New York and Boston.

The fit between land and water in the port area was improved,

expediting the critical commercial function of transporting goods

between ship and shore. Port activity increased in lockstep with

growing domestic demand; America was a growing nation.

Ships anchored in the harbor served as floating stores whose

wares were advertised by word-of-mouth ashore to the man on the

street — innkeepers, sail-makers, tailors, shoemakers, bricklayers,

schoolmasters, hatters, teamsters, bakers,

blacksmiths, clerks, barrel-makers, barbers,

millers, stevedores and ship carpenters.

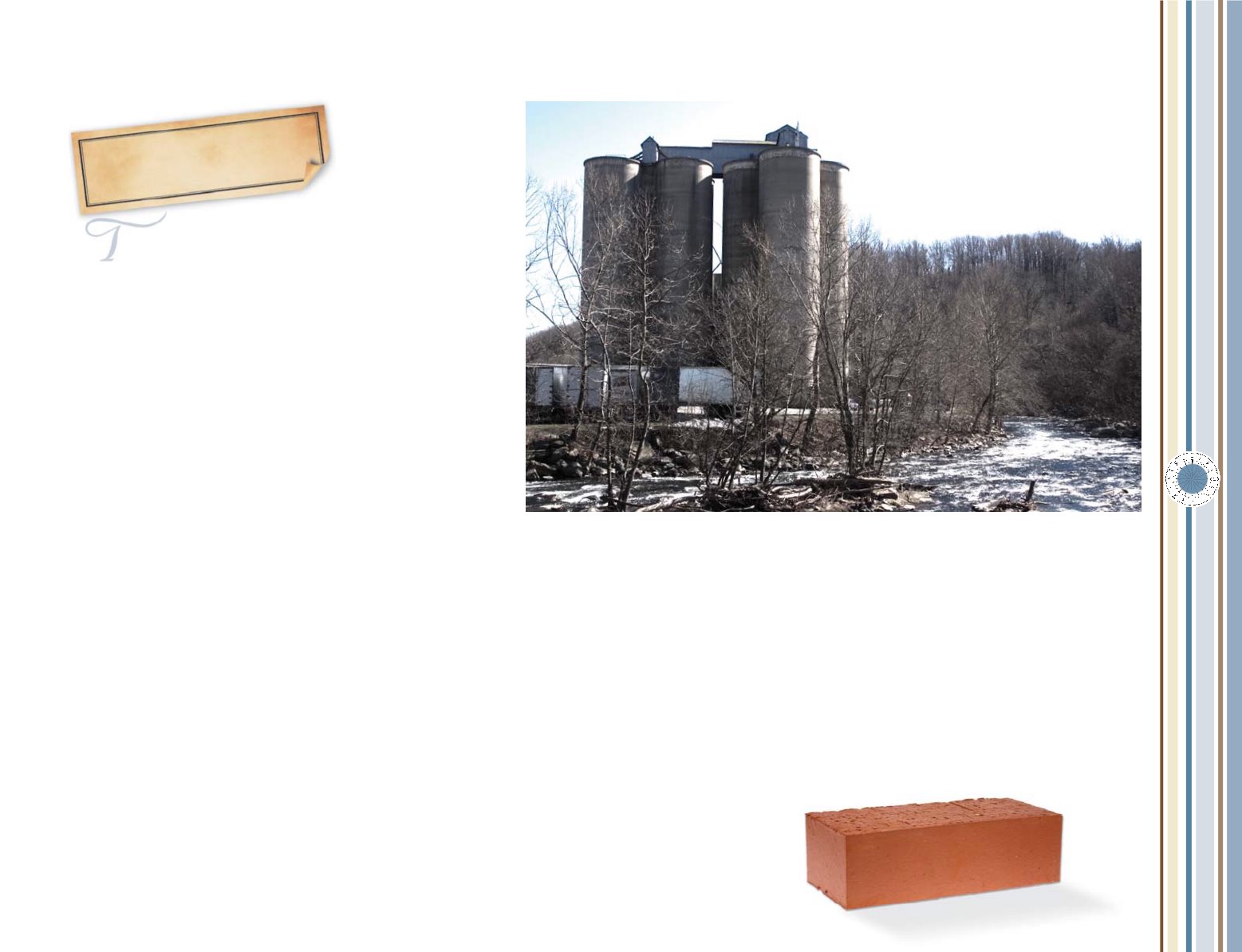

Above: TheWashington Flour

mill in Ellicott City still churns

out flour and cake mixes.

Below: Baltimore’s clayworks

supplied building bricks for

a city on the move. Due to its

quality and color, Baltimore

brick was in demand for the

facades of many elegant East

Coast mansions.

P

rime the

P

ump