7

hree-hundred years on the job without one hour off — that’s

24/7/365 x 300

—

is an enviable work history. And neither

history nor work is in short supply on Baltimore’s muscular

waterfront, where ships and cargoes just keep getting bigger.

But the history of the Port of Baltimore does not stop at the

water’s edge. Then, as now, the Port’s undercurrent surges beyond

the docks, sweeps through downtown, and widens as it moves

out across the state, bathing business and industry, washing

over Maryland culture, engaging all through dozens of points of

contact each and every day — even as most people outside the

maritime community are clueless about an industry which is

largely out of sight, and out of mind.

So the Port’s history cannot be confined to waterfront fixtures

which made it work so well for 300 years. Maritime’s influence on

the state and region is simply too vast, the impact of waterborne

dollars too profound.

Old salts and storied ships have their place. But the truer

telling of the Port’s history embraces the concurrent development

of metropolitan Baltimore and Maryland’s counties — the ben-

eficiaries of the Port’s mission of economic development — and

incorporates the Port’s social and cultural legacy.

Without the Port, Baltimore as we know it would not exist.

It would be something lesser and smaller. More likely, Baltimore

would have died a quick death.

Colonial Maryland was no garden of leisure. It was a hard

knock life, often short and brutal. Early attempts by Maryland

settlers to establish towns honoring British founder Lord Balti-

more (a.k.a. Cecil Calvert) on the Bush River in Harford County

and the Eastern Shore quickly failed. Even after the third attempt

finally took hold in 1724, on the marshlands where the Jones Falls

empties into the Patapsco River, Baltimore was a garden-variety

mud puddle in the wilderness.

Three decades later, Baltimore Town was hanging tough,

but still hanging: in 1754, its inventory included a few hundred

people, 24 houses, two taverns, one church — with a single finger

pier stuck into the shallows.

Humble as it was, the finger pier was a difference-maker for

Baltimore — that and its fortuitous proximity to the Patapsco

River Valley, the cradle of Maryland’s industrial revolution. The

mutually beneficial relationship between the Port and industry

was Baltimore’s breath of life. Without their collaborative heft,

Baltimore would have never approached its world-class status.

Baltimore Town wasn’t Maryland’s first official port; that

honor belonged to Humphrey’s Creek near Sparrows Point,

which Colonial legislators designated a Port of Entry in 1687.

Whetstone Point, near Fort McHenry, became Maryland’s second

Port of Entry 300 years ago in 1706 — the basis of the Port’s

2006 Tricentennial celebration. Both ports trafficked in tobacco,

Maryland’s first cash crop.

Facing page: Containers await

transport at Seagirt Marine

Terminal, one of 35 public and

private terminals serving the

Port of Baltimore. The mass

of the Port’s sprawling

facilities makes the better-

known Inner Harbor seem

downright diminutive.

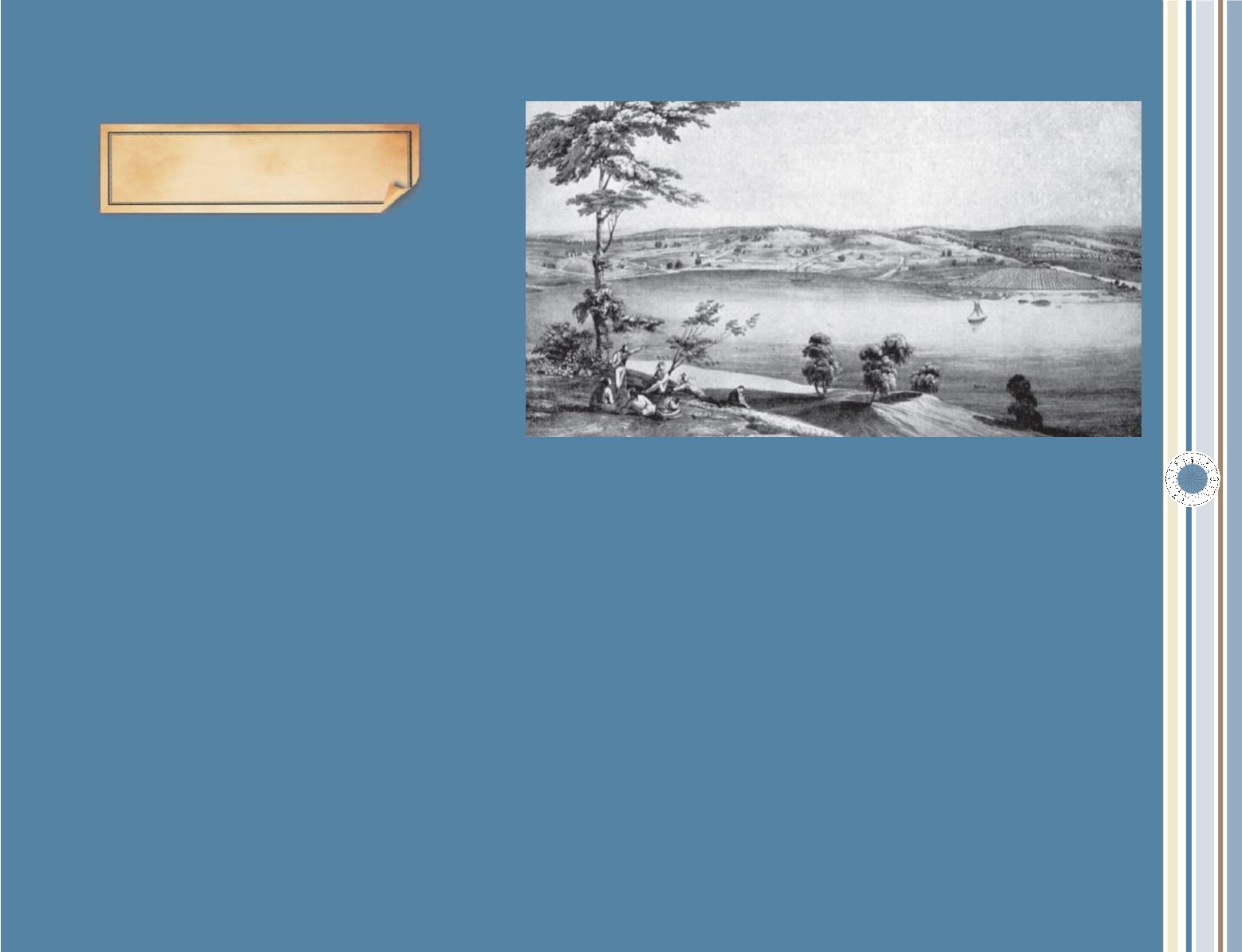

Above: John Moale’s 1752

depiction of the Port, looking

north from Federal Hill.

History of the Port

T